Even amid decline, restraints on Palm Beach County students among highest in Florida

Palm Beach Post | By Giuseppe Sabella | April 18, 2022

Palm Beach County public schools have recorded some of the most frequent use of physical restraints on students with disabilities in Florida, where state lawmakers are placing more scrutiny on the practice.

This school year, between August and February, the district reported 262 restraints, most, if not all, involving students with autism, emotional disorders or other disabilities. In February, 38% of restraints affected the county’s youngest students — between pre-kindergarten and third grade.

Most cases involve the controversial — and if done improperly, life-threatening — prone restraint, in which students are held on the ground with their heads to the side and their stomachs to the floor, usually by a team of several adults.

While the school district is on track to improve its past numbers, the recent seven-month total still makes it No. 4 for restraints in Florida, exceeded only by Volusia (265 restraints), St. Johns (338) and Polk (358).

Miami-Dade, the largest school district in Florida, reported only 47 restraint incidents during the same period, while Broward recorded fewer than 74.

In response, district leaders in Palm Beach County said that numbers alone can be deceiving, and that physical restraints are a last resort that can protect students and school employees in an emergency.

For example, that could mean a student was running away from campus and toward traffic, or that a student was throwing chairs at teachers or fellow classmates, said Kevin McCormick, the district’s director of exceptional student education.

Palm Beach County schools, he said, are often more diligent in reporting incidents than other Florida schools, and prone restraints — a position that can restrict breathing and cause death when done incorrectly — are done only by trained staff who make safety a priority.

“We have system-wide training. We do all we can to reduce it, and we will continue reporting the way we do and being transparent,” McCormick said.

But even when school staff protect a student’s physical safety during a restraint, psychological wounds remain a concern, said Kevin Golembiewski, director of advocacy, education and outreach for Disability Rights Florida, a not-for-profit corporation that provides legal help and other support to people with disabilities.

That can be especially true for students who face repeated restraints. In the 2019-20 school year, a Palm Beach County school restrained one student 48 times, and another school restrained a different student 68 times, according to district records.

High restraint numbers, Golembiewski said, represent a breakdown in the safeguards meant to curb certain behavior and vastly reduce the need for restraints. “We see restraints as rarely, if ever, appropriate on students with disabilities,” he continued.

The conversation on restraints is one that started in Palm Beach County more than a decade ago. Some parents asked the school board to ban prone restraints, while other families and school employees — describing students who injured themselves or attacked their teachers — said restraints were a necessary tool.

State lawmakers revived that conversation over the last year by passing two bills, both signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis, that limit restraints and promote more transparency.

Mechanical restraints with devices banned under new law

One banned the use of mechanical restraints, meaning straps or other devices, and the other requires schools to follow several new measures:

- Schools can use a restraint only after exhausting other alternatives.

- They can use restraints only when a serious risk of injury exists. The restraint has to be stopped as soon as possible.

- Restraints are not to be used as discipline or “to correct student noncompliance.”

- A crisis intervention plan is required for students restrained at least twice in a semester.

- Training is necessary for any staff who use restraints.

The new state requirements are similar to policies used by Palm Beach County schools for years. And though local schools have tracked their restraint numbers for years, the recent legislation requires the Florida Department of Education to post monthly restraint numbers for every district online.

As of Friday, the numbers for March were unavailable.

“You would think there’d be less restraints overall,” said Golembiewski, referring to the de-escalation policies in many Florida school districts. “But they continue to be an issue that we find to be concerning and something that affects students across the state.”

Prone restraints a longstanding debate in Palm Beach County and Florida

More than a decade ago, a school board member whose son had autism heard disturbing accounts of improper restraint from other families.

Among the family members was Joan Musumeci. At that time, she said a local middle school restrained her son, who has autism, about 90 times before she pulled him from the school system and filed a lawsuit.

She said Wednesday that those memories haunt the family to this day.

“My son, at times, would get very anxious and they were restraining him, a prone restraint most of the time, which would only upset him more,” Musumeci said.

“His behavior started changing at home,” the mother continued. “He wasn’t the same happy person he used to be. I’m not saying he was an angel, but they never should have done that to those kids. Restraint does not work.”

She reached a settlement with the school board in June 2013. Musumeci, who declined to name the settlement amount, said she accepted the agreement after a school district attorney threatened to countersue for legal fees.

In the years leading up to her settlement, between 2007 and 2011, the school board had already started to roll out new policies that called for regular updates on the number of restraints along with a host of de-escalation tactics.

The board members outlawed both mechanical and supine restraints, when students are held with their back to the ground, but they stopped short of banning the prone position.

Stuck between people who strongly supported or opposed the measure, the school board decided on a middle ground, making prone restraints a last resort to prevent “imminent risk of serious injury or death.”

Statewide and national efforts in the meantime have tried to put a stop to prone restraints altogether. A 2012 U.S. Department of Education report said prone restraints and “other restraints that restrict breathing should never be used because they can cause serious injury or death.”

The Keeping Students Safe Act, most recently introduced into Congress over the past two years, would have banned prone restraints in schools that accept federal funding. The legislation never advanced.

And a review by The Palm Beach Post found that 38 districts — at least half the school districts in Florida — say they don’t use prone restraints in their schools.

Some outlaw the practice in school board policy, others outlaw it in their procedures for students with disabilities, and some say it’s banned in their training and everyday practices.

Flagler, Walton and Hendry counties recently considered banning prone restraints in a formal policy, according to documents on file with the state Education Department.

Another four districts — Duval, Martin, Orange and St. Johns — told the Education Department they use prone restraints only in certain specialized schools.

Not all prone restraints are the same

Current policy in Palm Beach County schools bans “any restraint that restricts, or has the potential to restrict, a student’s breathing.” Some districts in Florida believe prone restraints meet that criteria.

Pinellas County Schools, for example, bans any method that would “restrict the breathing of a restrained student,” and it goes on to say that “this would include Prone Restraint.”

But in Palm Beach County, a prone restraint violates policy only when done improperly, the ESE director said.

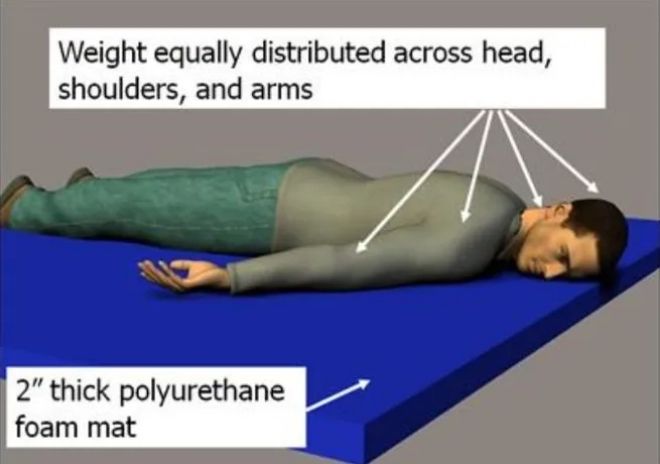

McCormick said all prone restraints are done on soft floor mats that have to be a certain size and thickness. A student is placed on his or her stomach, one side of their face rests on the mat, and their arms are held to the side.

Employees then loosen their grip within three seconds of the student calming down.

And any employee who uses a prone restraint must first complete a three day, 22-hour training program followed by annual recertification courses.

“We never hold their joints,” McCormick said. “We never hold them in a position that’s not natural. All the positioning is natural body positioning, and nobody is ever allowed to lay on a child.”

When Cornell University studied 38 deaths among children in the United States, each involving the prone position, the researchers noted a host of poor tactics.

Eight involved adults laying on top of the children, six involved adults crossing the children’s arms across their chests, and four involved adults sitting on the children.

“When any of these prone procedures have been implemented and it caused death, they were not implementing the procedures that we implement, including monitoring the student’s breathing and physiology,” McCormick said.

Palm Beach schools look to limit number of restraints

Golembiewski, of Disability Rights Florida, said restraints should be limited whenever possible, even if employees are well-trained.

“Regardless of what you might be doing with their limbs or the way their head is facing, if they’re on the ground, that can lead to being afraid of the school and the individual who used the restraint on them,” he said.

Using the example of a student running away from campus and toward traffic, Golembiewski said schools can find out what triggers the student, ensure the classroom is a comfortable place, provide sensory stimulation and create a safe space on campus where the student can run to if they feel like escaping.

It was also vital, he said, to ensure staff know the definition of a true emergency, and that students — each with their own unique needs — have individual plans on file.

Palm Beach County public schools already mandate behavior assessments and intervention plans for students who get restrained more than three times in a month. And thanks to updated Florida law, schools have to consider developing a crisis intervention plan for students after their second restraint in a single semester.

District policy also offers nearly a dozen items that employees have to consider before advancing to a restraint. Can they reassure the student with a light touch on the shoulder? Have they given the student options to re-direct their behavior? Is there a biological factor such as hunger at play?

But even with the best plans, any school district could struggle with turnover, understaffing, a lack of adequate resources or other obstacles that lead to problems,Golembiewski said.

McCormick acknowledged that no plan was perfect, and that Palm Beach County schools hoped to see their incident numbers drop. .

“Each kid is different, each scenario is different, and none of these situations are something that people want to do,” he said. “None of them are easy to implement because, when in crisis, things rarely go as planned. We just need to do all we can within our power to maintain safety and follow procedures.”

The school board voted Mach 23 to increase its agreement with Stuart-based Positive Behavior Supports Corp. by $42,000 to help create and carry out intervention plans that may reduce incidents.

When schools have a high number of incidents — including Addison Mizner Elementary with 11 restraints in October, Indian Ridge School with 10 in January and Coral Sunset Elementary with 10 in February — the district offers extra support.

And county-wide numbers are reviewed by the District Restraint Reduction Committee, which then comes up with plans to reduce incidents.

School board member Karen Brill, a longtime advocate for students with disabilities, receives a quarterly update on those numbers. The district, she said, is moving in the right direction.

Even with 262 cases as of February, the district is still poised to finish the school year with fewer restraints than the 2019-20 school year, when it documented about 423 incidents.

“Restraints are a last resort that are, unfortunately, the only resort we have to keep students and teachers safe sometimes,” Brill said.