Hillsborough needs drastic steps to tame school budget, officials say

Tampa Bay Times | by Marlene Sokol | January 12, 2021

TAMPA — At they rate they are going, Hillsborough County School District leaders said Tuesday, the nation’s seventh-largest school system might run out of money by June.

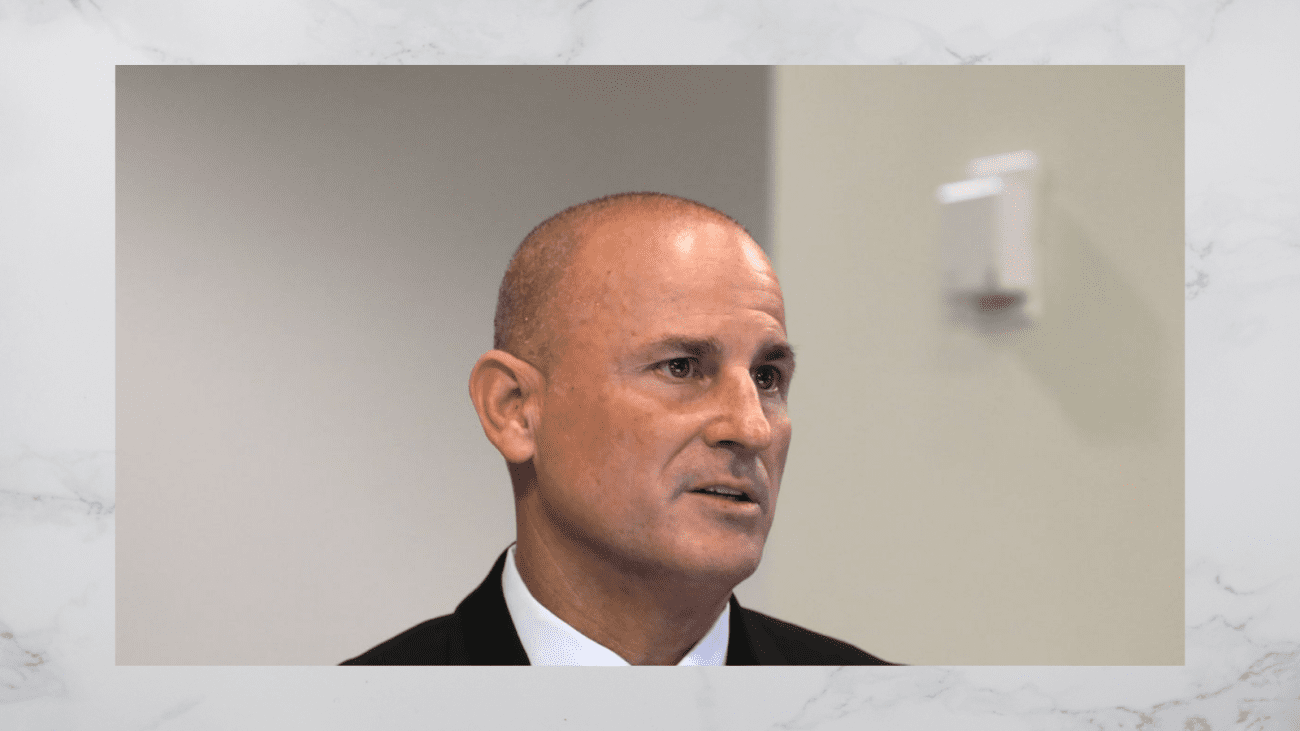

Expenses far exceed revenues, superintendent Addison Davis and deputy superintendent Michael Kemp told the School Board in a morning workshop. What’s more, they said, the district the district doesn’t have results to show for so much spending.

Compared with other like-sized Florida school districts with similar staffing, Hillsborough has 24 schools with D or F grades from the state while the others have hardly any. “We have to really look and question the return on investment,” Davis said.

This chart from Addison Davis and Michael Kemp’s slide show compares workforce of large Florida districts, and notes that Hillsborough has far more D and F schools than the others. [ Hillsborough County School District ]

Davis and Kemp offered a host of options to balance the operating budget and work through what could become a short-term cash crisis. Year-round employees might take some furlough days in the summer to save $3.5 million. In the coming school year, all employees might have to take unpaid days, to save another $20 million.

The district also might close or consolidate under-enrolled schools, or institute massive zoning changes to even out enrollment. “We can no longer afford to have schools of 200 students,” Davis said, estimating that 60 schools are at least a quarter empty.

Magnet schools, transportation costs and even security spending should be scrutinized, the administrators said.

Some of these remedies are long-term, but others will start immediately. Already, Davis said, he is looking at staffing levels school by school, as he did in the fall, to see which employees should be reassigned, or relegated to the hiring pool for the 2021-22 school year.

Over the course of that year he wants to save $148 million in staffing. That could mean a reduction of some 2,000 jobs, with the hope that many would happen through retirement or attrition.

While School Board members do not vote at workshops, four out of the seven signaled that they support Davis’ actions.

The other two — new members Nadia Combs and Jessica Vaughn — pushed back and said the district should focus more attention on the roughly $250 million it loses each year to the charter schools that educate more than 30,000 Hillsborough students. Karen Perez asked questions about other possible sources of income, and did not state a stronger position on either side.

Board member Melissa Snively, however, pointed out that state law greatly limits the district’s authority where charter schools are concerned.

Combs and Vaughn won their seats in November with the strong backing of the Hillsborough Classroom Teachers’ association, as did Henry “Shake” Washington. Chairwoman Lynn Gray had the union’s endorsement as well.

At one point on Tuesday, Vaughn tried to invite union executive director Stephanie Baxter-Jenkins up to the microphone to respond to Davis’ and Kemp’s remarks. But, advised that doing so would deviate from convention and set a precedent for future workshops, Gray said no.

Baxter-Jenkins did speak at the board’s 4 p.m. business meeting. “In making a point, I think the scare tactics of Dr. Kemp and, perhaps, the superintendent were unnecessary,” she said.

The facts in their presentation were not inaccurate, she said. But they gave an incomplete picture. For example, she said, there are numerous ways the district can raise money, should that become necessary, to meet payroll, including mortgaging some of the real estate that it owns. And that might not even be necessary, as the district is expecting $200 million in federal COVID-19 relief.

Earlier in the day, in a tweet, Baxter-Jenkins wrote, “we understand Florida is at the bottom for funding, nothing new. However, we will not accept furloughs for our members.”

Speaking briefly after the workshop, Baxter-Jenkins said the information Davis and Kemp presented was not technically inaccurate. But it was incomplete, she said.

Davis and Kemp contend that Hillsborough’s problems date back more than five years. They say when they arrived this summer, they walked into a system that relies on short-term grants, hires staff under those grants, and then folds them into the permanent workforce when the funding expires.

A study by the Council of the Great City Schools found that principals in Hillsborough were allowed to fill positions that had no funding. The report described one hiring freeze in which district leaders learned that of 1,129 vacant positions, only 424 were funded in the budget.

To cover these funding gaps, the district makes accounting adjustments to deliver a balanced budget to Tallahassee each year.

State law requires school districts to maintain reserve balances of at least 3 percent of anticipated revenue. But to get to that threshold, the district almost always transfers money into its operating budget from a capital fund. Such transfers, though legal, are frowned upon in the investment world, and the district must protect its credit rating for when it needs to take on debt.

Ultimately, administrators said, the money runs out. In the fall, the district took out a short-term loan of $75 million to meet payroll, a practice also employed by other districts, as tax revenues do not arrive at an even pace.

Some board members, including Perez, suggested that an influx of federal COVID-19 relief dollars will cover much of the shortfall, and that district leaders should do a better job lobbying the state government for more funding.

Davis and Kemp, while not disagreeing, said the board needs to pay attention to the long-term consequences of having a lopsided financial structure.

Kemp said, “It’s my responsibility to recommend to the board and the superintendent that, even if we identify a $100 million revenue stream, we absolutely must continue with the corrections… so we don’t have to have these conversations in the future.”

Another idea that has been floated is a local-option property tax, as Pinellas and other counties use to supplement teacher pay. Hillsborough’s recently enacted sales surtax can be used only for capital projects, not ongoing expenses.

But the district will not have another opportunity for such another tax referendum until the next general election in 2022.

Snively said that, given the current state of the economy, with many residents in danger of losing their homes, “I don’t believe we can ask our citizens for another tax increase.”

Featured image: Hillsborough County school superintendent Addison Davis has proposed drastic steps to tame the district’s budget. [ SCOTT KEELER | Times ]