To make up for COVID ‘lost learning,’ Central Florida schools invite thousands to summer school

Orlando Sentinel | by Leslie Postal | May 20, 2021

Aware COVID-19 disrupted education this past year, Central Florida school districts will host more expansive summer school programs in 2021, hoping to give students extra doses of reading and math — alongside fun classes in art, music, business, poetry and the like.

Across the region, thousands of more students than usual have been invited to summer programs that begin next month.

Orange County Public Schools, for example, hopes about 37,000 youngsters attend, up from the typical 10,000.

“This is a rigorous program compared to years past,” said Superintendent Barbara Jenkins, at a recent Orange County School Board meeting. “Intended not just to recover lost learning but also to accelerate and enrich our students. On top of all that, we’re going to make sure it’s fun as we need our children to come.”

Educators hope the fun will come from electives such as physical education and art and from hands-on activities in science, among others.

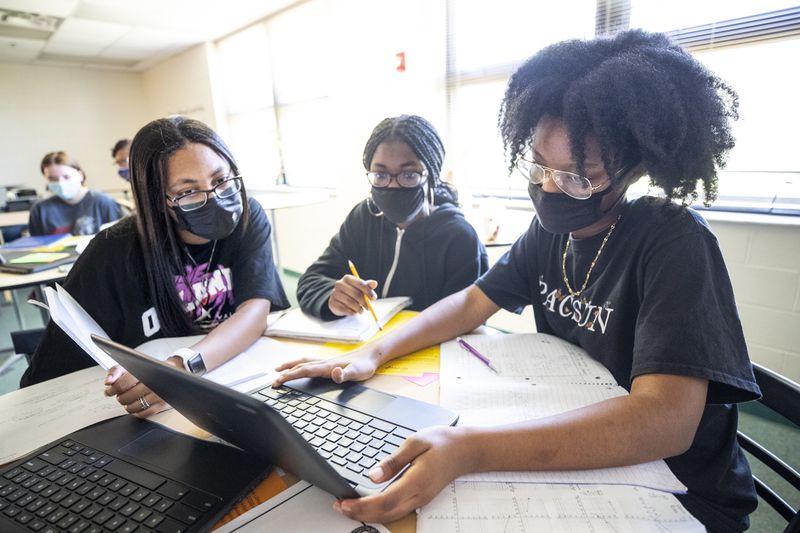

Summer school students will need to wear face masks in Orange. They will be optional in Lake. The Osceola County School Board has not yet decided when to end its current face mask rules. The Seminole board could decide June 22 to end its mask rule, but summer school would be under way then, so at least at the beginning students would need to wear them.

Educators want more students to attend summer school because they know more youngsters struggled academically this past year. Some found it hard to engage, or master concepts, as they studied online. Others were distracted by the upheaval the pandemic inflicted on their families.

Still, educators say it would be wrong to assume the entire 2020-21 school year was lost. Some students thrived, and many learned what they needed to in their classes.

“They’ve been rock stars … considering the hand they’ve been dealt this year,” said Music Brunetto, a civics teacher at Windy Hill Middle School in Clermont. “They’re doing an amazing job.”

Brunetto and several colleagues were on their Lake County campus this past weekend, offering review lessons to students readying for the state’s civics and algebra exams. Dozens of students attended, some riding bikes to campus for the practice session.

But plenty of school data worries school administrators:

– Statewide “progress monitoring” tests done in winter 2021 showed students in grades 3 to 5 were behind in math and reading compared with counterparts in 2020, according to the Florida Department of Education. The “drops in performance” were steeper for Black and Hispanic students than for white students. In Lake and Osceola, administrators say students’ math skills took the biggest hit.

– Report card grades were worse — sometimes much worse — for students doing classes online. In the fall, for example, 18% of Osceola high schools doing digital learning had an F in a class compared with less than 8% of those on campus.

– Students from low-income, Black and Hispanic families — who historically struggle the most in school — were more likely to be studying online this year, a trend the Orlando Sentinel reported in November. In October, for example, 68% of Florida’s white students and 40.5% of its Black students were on campus. That means some of the state’s neediest students weren’t getting the in-person lessons educators said would best help them learn.

– Thousands of 5-year-olds did not enroll in public school kindergarten classes this year. In Orange County, for example, 6,000 fewer students took the state’s annual “school readiness” test given to incoming kindergartners compared to the previous year, according to the Early Learning Coalition of Orange County. Many of the children who did not start kindergarten were in “under-resourced communities,” so a year at home may have been a year of little education.

“It’s been a year that’s been challenging for us,” said Emily Feltner, an assistant superintendent for Lake County schools. “There was some learning that just didn’t happen.”

Like other districts, Lake will use federal coronavirus relief money to help pay for an expanded summer school. The district hopes about 1,500 students attend, up from several hundred in past years.

Across the region, administrators plan to mix in enrichment classes in everything from art to entrepreneurship to science to make summer school engaging.

Because of the pandemic, more than half of Central Florida’s students started the school year online, doing classes from home, though many of them returned to campus as the year went on. Educators understand why parents kept their children home, but they also know that online many struggled to learn.

On campus, students dealt with new rules about face masks and social distancing and limits on what they could do in class or in some extracurricular activities.

“It’s a very weird year,” said Jason Lancy, an algebra teacher at Windy Hill, as he helped his students during the Saturday session.

Despite the challenges, he taught the required math standards and his students worked hard to master them, he said.

“Doing the best we can in a pandemic,” Lancy said. “It’s been a successful year, as successful as it could be.”

Katie Aldi, 13, a Windy Hill seventh grader, agreed. Despite COVID, school provided a chance to see friends and to work on “fun projects” in class. She liked her teachers and didn’t even mind getting up for a Saturday civics review.

“This was actually my favorite year,” she said.

Despite lots of worries about a “COVID slide,” plenty of students made expected academic gains this school year, said Robin Dehlinger, an executive director for elementary education for Seminole County Public Schools.

“We feel like the assumption is everyone has somehow been harmed, and it’s irreparable. We don’t see that,” Dehlinger said.

But there are more worries this year about “gaps” in student learning, she said, and so like its neighbors, Seminole will host expanded summer programs this year.

In Orange, a smorgasbord of summer school options will be offered, from “jump start” programs for incoming kindergartners to “advanced studies” programs for middle and high schoolers.

In Osceola County, the school district hopes summer enrollment tops 9,000 students, about three times as many children as typically attend. All the programs will work in hands-on activities, if possible.

“We know the kids have had an awful lot of screen time this year,” said Superintendent Debra Pace.

Summer school invitations have met with “strong support” from parents, who recognize the challenges this year posed, Pace said. “Kids missed some fundamental pieces, and it’s been hard to catch up.”

But the summer offerings also will be less intensive than regular school, running for half a day and for four days a week, a recognition that both students and staff also need a break.

“It is very true that everybody is tired,” Pace said. “It’s been a very long school year.”

Featured image: Marianela Ramos, Sade Joseph and Azaria Brown work on a question during algebra review at Windy Hill Middle School in Clermont, Fla., Saturday, May 15, 2021. (Orlando Sentinel Photo/Willie J. Allen Jr.) (Willie J. Allen Jr./Orlando Sentinel)